Caravaggio Painting Reproductions 1 of 4

1571-1610

Italian Baroque Painter

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio was born on 29 September 1571, near Milan, into circumstances that soon demanded resilience. His father served as an architect-decorator to the local nobility, but the family’s stability was short-lived. In 1576, plague forced them to relocate to the town of Caravaggio, where both Caravaggio’s father and grandfather died the following year. His mother, raising five children amid financial strain, died in 1584, the same year he began his apprenticeship under Simone Peterzano in Milan. This training placed him within a tradition rooted in Venetian influences, yet he absorbed a more sober Lombard style that valued realistic attention to detail over the elegance typical of central Italy.

From his earliest years, Caravaggio’s focus remained on the human form as it truly appeared. This inclination was reinforced during his apprenticeship, where he gained the habit of observing from life rather than relying on elaborate preparatory drawings. Late in his teens, around 1592 or 1593, he left Milan for Rome, propelled by unsettled quarrels and an eye for opportunity. He arrived impoverished, taking small commissions that demanded he paint fruit and flowers. That lowly labor did little to dim his ambitions. His determination soon led to friendships with established artists and collectors, who recognized both his promise and the startling realism of his canvases.

Caravaggio’s reputation advanced rapidly. Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte took him under protection, offering the young painter a chance to execute genre scenes of musicians and card players for the refined company he kept. In these works, the precision of the natural world - be it a bruised peach or a youth’s rumpled sleeve - was brought to the fore with a theatrical quality of light and shade. This approach would soon become known as tenebrism, an extreme form of chiaroscuro that carved figures from darkness by stark beams of illumination. Rome at the time sought art that could persuade and move, and Caravaggio’s style, both devotional and deeply human, began to gain commissions for significant religious subjects.

His work on the Contarelli Chapel, completed around 1600, secured public acclaim. The commission included "The Calling of Saint Matthew" and "The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew," paintings whose dynamism lay in the vigorous contrast of light and shadow. His figures looked like everyday people, immersed in dingy taverns or shadowy corners, yet invested with spiritual gravity. Not all patrons, however, warmed to this intense realism. Certain works, such as the first version of "Saint Matthew and the Angel," met criticism for depicting sacred figures in overly familiar or unvarnished guises. Still, Caravaggio’s daring sensibility found favor with many collectors and church officials, ensuring a steady flow of commissions.

Despite artistic triumphs, his personal life was fraught with conflict. He was quick to take offense, prone to brawls, and frequently arrested for various scrapes with the law. A confrontation in 1606 ended in the death of a young man named Ranuccio Tommasoni. Whether it was a duel over gambling debt, romantic rivalry, or broader tensions, Caravaggio was sentenced to death. His allies could no longer shield him, and he fled Rome, never to return freely. This period of exile took him to Naples, where he again received crucial support from the powerful Colonna family. Commissions followed, most notably "The Seven Works of Mercy," which combined multiple compassionate acts within a single tumultuous scene. Yet Caravaggio, still restless, left Naples for Malta in hopes that the influential Knights of Saint John might procure his pardon.

On Malta, Caravaggio painted "The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist," an ambitious work that revealed his signature style at its most monumental. Impressed by his talents, the Grand Master inducted him as a Knight. However, another violent altercation soon saw Caravaggio imprisoned, and he staged a dramatic escape, ending up in Sicily. There, he reconnected with friends and painted altarpieces in Syracuse and Messina. These compositions conveyed an ever-deepening sense of isolation, the figures enveloped in cavernous darkness. Observers remarked on his erratic behavior - tearing up canvases over minor criticisms, refusing to sleep except fully clothed, and harboring unshakable fears of pursuit. Nevertheless, his artistry continued to inspire local patrons.

By 1609, he returned to Naples to wait for a pardon that he believed was close at hand. Yet he was nearly killed in a street ambush, disfigured, and rumors of his death spread. In the last months of his life, he painted works like "Salome with the Head of John the Baptist" and "David with the Head of Goliath," where the severed heads bore his own features. These final images seem charged with personal plea, as though he was wrestling with guilt and appealing to powerful figures, including Cardinal Scipione Borghese, for a reprieve. When word reached him that reconciliation with Rome might be achieved, Caravaggio set out by boat. Accounts diverge on the exact sequence that followed, but most agree he died of fever around 18 July 1610, near Porto Ercole on Italy’s western coast.

Caravaggio’s formative role in shaping Baroque painting would be recognized centuries later. His unflinching study of models drawn directly from life - prostitutes, laborers, or acquaintances - and the pronounced theatrical lighting he championed would pave the way for generations of painters seeking a more immediate, human engagement with art. While he fell out of favor soon after his death, modern scholarship has restored him to an eminent position in the narrative of Western art. His life, marked by fervent creativity and tumultuous misadventures, underscores the tension between rigorous formal innovation and personal instability. It is the interplay of these forces that defines his singular place in the history of painting.

From his earliest years, Caravaggio’s focus remained on the human form as it truly appeared. This inclination was reinforced during his apprenticeship, where he gained the habit of observing from life rather than relying on elaborate preparatory drawings. Late in his teens, around 1592 or 1593, he left Milan for Rome, propelled by unsettled quarrels and an eye for opportunity. He arrived impoverished, taking small commissions that demanded he paint fruit and flowers. That lowly labor did little to dim his ambitions. His determination soon led to friendships with established artists and collectors, who recognized both his promise and the startling realism of his canvases.

Caravaggio’s reputation advanced rapidly. Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte took him under protection, offering the young painter a chance to execute genre scenes of musicians and card players for the refined company he kept. In these works, the precision of the natural world - be it a bruised peach or a youth’s rumpled sleeve - was brought to the fore with a theatrical quality of light and shade. This approach would soon become known as tenebrism, an extreme form of chiaroscuro that carved figures from darkness by stark beams of illumination. Rome at the time sought art that could persuade and move, and Caravaggio’s style, both devotional and deeply human, began to gain commissions for significant religious subjects.

His work on the Contarelli Chapel, completed around 1600, secured public acclaim. The commission included "The Calling of Saint Matthew" and "The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew," paintings whose dynamism lay in the vigorous contrast of light and shadow. His figures looked like everyday people, immersed in dingy taverns or shadowy corners, yet invested with spiritual gravity. Not all patrons, however, warmed to this intense realism. Certain works, such as the first version of "Saint Matthew and the Angel," met criticism for depicting sacred figures in overly familiar or unvarnished guises. Still, Caravaggio’s daring sensibility found favor with many collectors and church officials, ensuring a steady flow of commissions.

Despite artistic triumphs, his personal life was fraught with conflict. He was quick to take offense, prone to brawls, and frequently arrested for various scrapes with the law. A confrontation in 1606 ended in the death of a young man named Ranuccio Tommasoni. Whether it was a duel over gambling debt, romantic rivalry, or broader tensions, Caravaggio was sentenced to death. His allies could no longer shield him, and he fled Rome, never to return freely. This period of exile took him to Naples, where he again received crucial support from the powerful Colonna family. Commissions followed, most notably "The Seven Works of Mercy," which combined multiple compassionate acts within a single tumultuous scene. Yet Caravaggio, still restless, left Naples for Malta in hopes that the influential Knights of Saint John might procure his pardon.

On Malta, Caravaggio painted "The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist," an ambitious work that revealed his signature style at its most monumental. Impressed by his talents, the Grand Master inducted him as a Knight. However, another violent altercation soon saw Caravaggio imprisoned, and he staged a dramatic escape, ending up in Sicily. There, he reconnected with friends and painted altarpieces in Syracuse and Messina. These compositions conveyed an ever-deepening sense of isolation, the figures enveloped in cavernous darkness. Observers remarked on his erratic behavior - tearing up canvases over minor criticisms, refusing to sleep except fully clothed, and harboring unshakable fears of pursuit. Nevertheless, his artistry continued to inspire local patrons.

By 1609, he returned to Naples to wait for a pardon that he believed was close at hand. Yet he was nearly killed in a street ambush, disfigured, and rumors of his death spread. In the last months of his life, he painted works like "Salome with the Head of John the Baptist" and "David with the Head of Goliath," where the severed heads bore his own features. These final images seem charged with personal plea, as though he was wrestling with guilt and appealing to powerful figures, including Cardinal Scipione Borghese, for a reprieve. When word reached him that reconciliation with Rome might be achieved, Caravaggio set out by boat. Accounts diverge on the exact sequence that followed, but most agree he died of fever around 18 July 1610, near Porto Ercole on Italy’s western coast.

Caravaggio’s formative role in shaping Baroque painting would be recognized centuries later. His unflinching study of models drawn directly from life - prostitutes, laborers, or acquaintances - and the pronounced theatrical lighting he championed would pave the way for generations of painters seeking a more immediate, human engagement with art. While he fell out of favor soon after his death, modern scholarship has restored him to an eminent position in the narrative of Western art. His life, marked by fervent creativity and tumultuous misadventures, underscores the tension between rigorous formal innovation and personal instability. It is the interplay of these forces that defines his singular place in the history of painting.

79 Caravaggio Paintings

The Lute Player c.1595

Oil Painting

$3812

$3812

Canvas Print

$73.13

$73.13

SKU: CMM-2768

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 94 x 119 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 94 x 119 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Bacchus c.1597

Oil Painting

$4467

$4467

Canvas Print

$82.14

$82.14

SKU: CMM-2769

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 95 x 85 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 95 x 85 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Boy with a Basket of Fruit c.1593/94

Oil Painting

$3487

$3487

Canvas Print

$90.30

$90.30

SKU: CMM-2770

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 70 x 67 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 70 x 67 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Sick Bacchus (Self-Portrait as Bacchus) c.1592/93

Oil Painting

$2681

$2681

Canvas Print

$109.80

$109.80

SKU: CMM-2771

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 67 x 53 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 67 x 53 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Boy Bitten by a Lizard c.1595/00

Oil Painting

$2645

$2645

Canvas Print

$101.02

$101.02

SKU: CMM-2772

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 66 x 49.5 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 66 x 49.5 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Penitent Magdalen c.1598

Oil Painting

$2809

$2809

Canvas Print

$127.54

$127.54

SKU: CMM-2773

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 122.5 x 98.5 cm

Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 122.5 x 98.5 cm

Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Italy

The Cardsharps (I Bari) c.1595/96

Oil Painting

$4166

$4166

Canvas Print

$67.34

$67.34

SKU: CMM-2774

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 90 x 112 cm

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 90 x 112 cm

Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA

The Musicians (Concert) c.1594/95

Oil Painting

$4359

$4359

Canvas Print

$71.26

$71.26

SKU: CMM-2775

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 92.1 x 118.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 92.1 x 118.4 cm

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt c.1595

Oil Painting

$5116

$5116

Canvas Print

$125.58

$125.58

SKU: CMM-2776

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 135.5 x 166.5 cm

Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 135.5 x 166.5 cm

Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Italy

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy c.1594/95

Oil Painting

$2683

$2683

Canvas Print

$112.18

$112.18

SKU: CMM-2777

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 93.9 x 129.5 cm

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, USA

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 93.9 x 129.5 cm

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, USA

The Supper at Emmaus 1601

Oil Painting

$5300

$5300

Canvas Print

$110.64

$110.64

SKU: CMM-2778

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 141 x 196.2 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 141 x 196.2 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

The Fortune Teller (La Zingara) c.1596/97

Oil Painting

$3512

$3512

Canvas Print

$68.02

$68.02

SKU: CMM-2779

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 99 x 131 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 99 x 131 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

The Conversion of Mary Magdalen c.1597/98

Oil Painting

$3617

$3617

Canvas Print

$115.04

$115.04

SKU: CMM-2780

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 100 x 134.5 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, USA

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 100 x 134.5 cm

Detroit Institute of Arts, Michigan, USA

Saint Catherine of Alexandria c.1598/99

Oil Painting

$3812

$3812

Canvas Print

$72.45

$72.45

SKU: CMM-2781

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 173 x 133 cm

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 173 x 133 cm

Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid, Spain

Judith Beheading Holofernes c.1599/00

Oil Painting

$5139

$5139

Canvas Print

$69.72

$69.72

SKU: CMM-2782

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 145 x 195 cm

Palazzo Barberini, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 145 x 195 cm

Palazzo Barberini, Rome, Italy

The Conversion of Saint Paul c.1600/01

Oil Painting

$4242

$4242

Canvas Print

$71.08

$71.08

SKU: CMM-2783

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 230 x 175 cm

Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 230 x 175 cm

Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter c.1600/01

Oil Painting

$6401

$6401

Canvas Print

$71.60

$71.60

SKU: CMM-2784

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 230 x 175 cm

Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 230 x 175 cm

Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, Italy

Basket of Fruit c.1597/00

Oil Painting

$2149

$2149

Canvas Print

$74.15

$74.15

SKU: CMM-2785

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 54.5 x 67.5 cm

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 54.5 x 67.5 cm

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Milan, Italy

Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Grand Master of ... 1607

Oil Painting

$3772

$3772

Canvas Print

$61.71

$61.71

SKU: CMM-2786

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 194 x 134 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 194 x 134 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Amor Victorious (Cupid) c.1601/02

Oil Painting

$4565

$4565

Canvas Print

$67.68

$67.68

SKU: CMM-2787

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 156.5 x 113.3 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 156.5 x 113.3 cm

Gemaldegalerie, Berlin, Germany

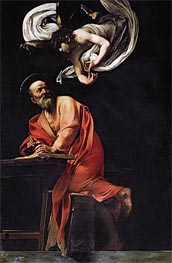

Saint Matthew and the Angel 1602

Oil Painting

$3461

$3461

Canvas Print

$61.71

$61.71

SKU: CMM-2788

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 295 x 195 cm

San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 295 x 195 cm

San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, Italy

Saint John the Baptist 1602

Oil Painting

$3886

$3886

Canvas Print

$68.02

$68.02

SKU: CMM-2789

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 129 x 95 cm

Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 129 x 95 cm

Musei Capitolini, Rome, Italy

The Betrayal of Christ (Taking of Christ) 1602

Oil Painting

$5373

$5373

Canvas Print

$73.13

$73.13

SKU: CMM-2790

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 135.5 x 169.5 cm

National Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 135.5 x 169.5 cm

National Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

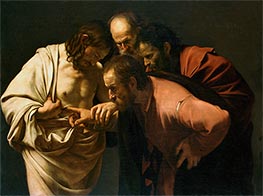

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (Doubting Thomas) c.1601

Oil Painting

$4181

$4181

Canvas Print

$69.56

$69.56

SKU: CMM-2791

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 108.5 x 145 cm

Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam, Germany

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio

Original Size: 108.5 x 145 cm

Sanssouci Palace, Potsdam, Germany