George Caleb Bingham Painting Reproductions 1 of 1

1811-1879

American Realist Painter

George Caleb Bingham (March 20, 1811 - July 7, 1879) - 19th century American painter of the American West. The majority of Bingham's paintings and virtually all of his drawings are held in American museums, with the largest selection of paintings at the St. Louis Museum of Art. No museums outside of the United States hold any works by Bingham. Other than portraits, his available paintings are rare and are seldom found at galleries or at auction.

George Caleb Bingham was born in Augusta County, Virginia on March 20, 1811 on his grandfather's farm (with its prosperous working mill), son of Henry Vest and Mary (Amend) Bingham. In 1819, because of a failed investment, the Bingham family moved to Missouri Territory and young George grew up variously in Franklin, Arrow Rock, and Boonville.

When the Binghams moved to a prospering Franklin in 1819, then just two years established on the banks of the Missouri River, there were still vestiges of Spanish, French, and English influence and Osage Indians roamed the countryside (see "The Concealed Enemy"). Here in 1820, nine-year-old George as he remembered fifty years later was first inspired to be an artist by Chester Harding, who had taken lodging at Henry Bingham's inn The Square and Compass. Harding, who became one of America's finest portraitists, had been in St. Charles County near St. Louis painting a portrait of the aged Daniel Boone, the legendary folk hero whose trailblazing opened up the West for settlement. Having come upriver to Franklin looking for more commissions, Harding was also putting the finishing touches to the Boone portrait. Young George, already showing signs of drawing ability and having an interest in art, was assigned by his father to assist Harding in his needs as he daily worked on the Boone portrait. George no doubt had the exciting opportunity as well to study the various sketches and paintings the artist carried with him. Bingham later in life wrote: "The wonder and delight with which Harding's works filled my mind impressed them indelibly upon my then unburdened memory."

In 1823, George's father Henry Bingham died of malaria. This tragedy left his wife Mary and their children little else but their farm across the river from Franklin in Saline County, near Arrow Rock, fortunately where Henry's brother John and his family had recently settled.

During the next five years in Arrow Rock, young George was reportedly tutored by Rev. Jesse Green, a cabinet maker and Methodist minister. From 1828-32, George lived in nearby Boonville, apprenticed to Rev. Justinian Williams (yet another cabinet maker who was also a Methodist minister). The early influences of woodworking with its attendant strict craftsmanship and geometric constructions, as well as that of Biblical literature with its moral teachings and rich narratives, may suggest further insights into the early development of Bingham's artistic consciousness.

As he matured into his teens, George also gave serious consideration to the professions of lawyer and preacher (which he had personally practiced, preaching here and there as a student of the two Reverends). These early ambitions could be seen to characterize his enduring combative and moralistic personality. However, the idea of becoming a painter interrupted these musings and began to materialize as a result of a second meeting, during his apprenticeship in Boonville, with his old friend Chester Harding who gave him some brushes and urged him to try his hand at painting a portrait.

Bingham's artistic career as a self taught portrait painter began in earnest a little later in Arrow Rock. His early style of portraiture, seen in 1834-40 examples, were skillfully crafted, strongly characterized, and far superior to the work of most provincial artists of the period. His later portraits from the 1840s into the 1870s generally conveyed a softer tone and a straighforward likeness. Many, from his early to his late period, stand as exceptional studies of their subjects.

Perhaps the fine quality of the two late examples could be tied additionally to the affection George had for Rollins and Ream. By 1878, near the end of his life, Bingham had painted close to 500 portraits.

Portraiture was by far George's most prolific artistic genre, producing a steady income throughout his career and "kept the pot boiling", as the artist acknowledged. But he also admitted to the pleasures of friendship and personal relations that developed from painting portraits and he unquestionably gained social status from the outset of his career by his choice of subjects, most of whom represented a veritable Who's Who of 19th century Missourians. Most important among Bingham's portrait-fostered friendships was one that established an extraordinary lifelong bond with Major James Sidney Rollins, a practicing Columbia, Missouri lawyer close in age to George, whose portrait the artist first painted in 1834. Rollins a wealthy and powerful Missouri politician and "Father of the University of Missouri" was Bingham's first patron and he went on to become a brotherly confidant, advisor, political ally, and financial backer to the end of Bingham's life. In excerpts from several late letters, an ailing Bingham writes to Rollins: "I shall never be able to repay you for a ...friendship such as few men have the good fortune to be blessed with on this earth...No man could be blessed with a truer and more constant friend that I have ever found in yourself ...[a friend who had always given him ]...the tenderest solicitude of a brother."

In 1845 Bingham began the series of narrative scenes of frontier life upon which his reputation rests. "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri", the earliest of his masterworks, is still considered his best and most iconic painting. It is also the simplest of his multifigure scenes: it depicts a grizzled pipe-smoking fur trader, a smiling youth, and a tethered baby bear, all posed in a long thin dugout canoe. Out of the wilderness they come, gliding silently and eternally by on the placid water, gazing at you and you at them. Indeed, the painting may have been animated in Bingham's mind like a scene from the moving-picture "panoramas" of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, in vogue since the first 1839-40 exhibitions in nearby Louisville which George possibly attended during a political trip to Washington, D.C. Bingham traveled constantly and big cities like St. Louis, Philadelphia, Washington, New York were familiar environments where he worked and lived and found artistic stimulation.

Riverboatmen, considered a rough and carefree bunch, were a more familiar sight than fur traders. In his first depiction of them "The Jolly Flatboatmen" (1846) Bingham showed the hard working boatmen enjoying themselves as their day on the river begins. With their celebration invitingly filling most of the picture plane, the spectator glides along behind them enjoying the moment. Its vicarious joy is irresistible; its classically organized and finely crafted composition becomes for the viewer a clear and memorable image.

It is instructive to recognize in regard to Bingham's style that no 19th century American artist created paintings with a more conscious geometrical structure of forms or with a more conscious embrace of the classical Renaissance tradition, a tradition which importantly stressed the artist's use of model drawings. Bingham used figurative drawings as an integral part of his painting procedure; sometimes as side by side models, sometimes as transfer drawings which were traced onto primed canvas. His drawings went with him everywhere as precious sources for his paintings.

Self taught, Bingham learned deep lessons from the old masters which he no doubt first experienced as prints, perhaps after Raphael's paintings or Greco-Roman sculpture or from instruction books like Francis Nicholson's "The Practice of Drawing and Painting Landscapes from Nature..."(1823). Nicholson cited landscape models such as Poussin, Claude, Salvator Rosa and Richard Wilson, and offered such instructions as: "The foundation of drawing and painting from nature should be laid by studying and copying the works of the best masters, in order to ascertain the methods of practice, and principles of construction. With such assistance, the learner will acquire the power of seeing what is most perfect in nature..."

Notable examples of Bingham's landscape paintings emerge particularly from the early 1850s in a variety of styles. "The Storm", "Horse Thief", and "Deer in Stormy Landscape" all suggest a strong direction from Thomas Cole and the period of the Cole revival after the artist's early and widely lamented death in 1848, with "Horse Thief" coming closest to Cole's allegorical landscapes. In a more conservative direction, closer to English country scenes and American counterparts like Joshua Shaw, Thomas Doughty, and Asher Durand, "Landscape with Waterwheel and Boy Fishing" and "View of a Lake in the Mountains" offer fine examples and suggest youthful reveries drawn from Bingham's growing up in Virginia and Missouri. As only 25 of Bingham's 50 recorded landscapes have been located, his complete achievement in this field, in which he ranged widely, must await a later judgment.

Poussin's works clearly inspired Bingham's thinking about figural compositions, as well as about landscape. George learned well from the masters: his compositions with figures are exceptionally well organized and skillfully posed; his landscapes are arranged clearly and distinctly. Pyramidal formations of figures and a balanced geometrical construction consistently bring a classical order to Bingham's narrative and landscape paintings. His style could be succinctly stated a straightforward realistic manner based on geometrical principles and classical models.

Bingham was inspired by many artistic predecessors but his genius invariably transformed suggestion from others into his own original statement.

Starting in 1847 and in a more developed way in the early 1850s, Bingham began his "Election" series of paintings illustrating America's democratic process and the political life of the Western frontier. The success of these election pictures in their public exhibitions encouraged Bingham to commission engravings of them and this continued to spread his fame around the nation. These prints also importantly supported and illustrated the notion of Missouri's coming of age within the American political framework, having just become a state in 1820 . A number of Bingham's political pictures exist in duplicate since he made one copy available for exhibition while a second was in the hands of an engraver.

Two of the most notable Election pictures "The County Election" and "The Verdict of the People" involved dozens of carefully organized interacting figures, many of which were modeled from drawings that illustrated a wide variety of people of many physical types, ages, facial features, expressions, and body positions. The drawings with very little variation in size would then be creatively placed, transferred or modeled onto the canvas, and then painted. Bingham's artistic method throughout his career involved use of a portfolio of model drawings, almost all of them figurative, many of which he reused interchangeably. Virtually all of Bingham's extant drawings are deposited in museums across Missouri.

Surprisingly, little evidence of preliminary landscape or portrait sketches have been found, suggesting George must have painted or drew the landscape elements and portraits directly onto the canvas. It is probable that he also used available photographs to assist with some of his portrait subjects after 1847.

The existence of Bingham's own early use of photographic records, beginning in 1847 with daguerreotypes of a few of his important paintings, points to an unusual and possibly unique procedure for an American artist of the period. By so doing, Bingham preserved the appearance of a lost picture, "The Stump Orator" (1847) the earliest of the Election series and in all likelihood used its photographic record along with saved drawings to reconstruct this complicated composition as a new work in 1853-54 titled "Stump Speaking".

The political genre undoubtedly drew Bingham to study the series of election subjects by the famous English artists William Hogarth (1697-1764) and Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), from whose widely reproduced works he clearly found inspiration. While Bingham's paintings do not have the wholly satirical overtones of Hogarth's, they do have an honest social and political presence of real, imperfect, and animated people interacting in what his French contemporary Balzac called "The Human Comedy". The paintings no doubt drawn from Bingham's own well considered experiences as voter, party worker, and elected politician reflect the rough hewn political life of Missouri frontier towns and other American places.

Bingham's genre and landscape paintings of the "exotic West" became popular in the East largely due to the support of the influential New York-based American Art-Union (active 1839-51). The AAU purchased and distributed George's paintings, and occasionally distributed engravings of them, to a national membership by lottery. The AAU had a fee-based membership which by 1849 numbered close to 20,000 members. Each year, members received an engraving of a painting by an American artist as well as a chance to win an original painting or sculpture at an annual lottery. Artists were also invited to exhibit and sell works at the gallery in New York City. Bingham's commercial success began at the AAU in 1845 with their purchase of "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri" and "The Concealed Enemy" as well as two landscapes "Cottage Scenery" and "Landscape: Rural Scenery". In 1846, "Jolly Flatboatmen" was purchased and gained enormous national popularity when it was engraved and distributed in 1847 to 10,000 subscribers. In a seven year period, the AAU purchased twenty of George's paintings. Along with Bingham, the AAU helped further the careers of William Sidney Mount, Richard Caton Woodville, George Inness, and Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze.

Although his life was dedicated primarily to painting, Bingham was always acutely aware of the significant events in the nation's evolving history and, on more than one occasion, felt impelled to be something more than an armchair observer. His early self-taught training in law and his skill as a public speaker prepared him for the political arena, but it was more his deep-rooted moral convictions about right and wrong and a strong sense of public duty that stimulated him from time to time to leave his chosen career and seek public office and work for the public good. Highlights of Bingham's political career, not including the many times he was a candidate for public office, can be briefly summarized: 1848, elected to a seat in the Missouri state legislature as representative from Saline County; 1862-1865, during the Civil War, appointed Missouri state treasurer; 1874, appointed president of Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners; 1875, appointed adjutant-general of Missouri by the governor (which led to his being called "General Bingham" toward the end of his life).

In 1856, Bingham with his wife and daughter Clara sailed for Europe, first to Paris, which he found alien and inhospitable and expensive and even the Louvre disconcerting. George and his family then went on to a sojourn in Dusseldorf, where he completed full-length portraits of Washington and Jefferson (a commission from the Missouri State Legislature, both now destroyed by fire); the second of three related flatboatmen paintings, "Jolly Flatboatmen in Port" (1857); "Moonlight Scene: Castle on the Rhine"(1857, Private Collection); and probably other unrecorded works.

Dusseldorf , compared to Paris, was a manageable city of 30,000 and a famous art center that had attracted, interestingly enough, such aspiring German-American artists as Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Carl Wimar, and Albert Bierstadt all of whom had been born in Germany and emigrated to the United States as children, only to return to Germany to study and in Leutze's case to live in Dusseldorf for many years where he also became a noted teacher. From the 1840s through the 1850s other American artists such as T. Worthington Woodridge, Richard Caton Woodville, and Eastman Johnson also studied in Dusseldorf. Leutze, as teacher and great friend of visiting American artists, was a first stop for American expatriates, and Bingham, although a mature and established painter, was no exception. George wrote to his friend Rollins back in Columbia, Missouri: "Immediately upon our arrival in Dusseldorf, I called upon Leutze, the famous painter, who received me as cordially as if I had been a brother, and without a moment's delay assisted me in finding a Studio, and introduced me to one of his American pupils through whose guidance I shortly obtained accommodations of the best kind, and upon the most reasonable terms."

Upon his somewhat reluctant return to the United States in 1859 in the wake of the death of his wife Eliza's father Bingham became increasingly busy in Missouri with politics. Most of his diminishing artistic production consisted of portrait commissions, with an occasional genre or history painting, most notably the legendary "Martial Law or Order No. 11". George continued to live a restless nomadic life, constantly traveling in search of portrait commissions, and residing all over Missouri.

In 1877, thanks once again to Rollins, Bingham now in poor health was appointed the first Professor of Art at the University of Missouri's newly established School of Art in Columbia, a largely honorary position that allowed students to observe him at the easel from time to time and to seek limited instruction.

Weakened from a bout with pneumonia in February 1879 and in fragile health thereafter, Bingham died at age 68 in his home in Kansas City on July 7, from "cholera morbus" (a disease, it is noted, that is usually caused by imprudence in diet or by gastrointestinal disturbance).

George Caleb Bingham is buried in the Union Cemetery in Kansas City under a tall monument commissioned by his third wife, the notable Mattie Livingston Lykins. The monument bears a medallion-like portrait bust of the artist carved in relief and an almost obscured inscription: "Eminently gifted, almost unaided he won such distinction in his profession that he is known as the Missouri artist." In an 1837 letter to James Rollins, Bingham wrote his credo at the beginning of his career: "There is no honorable sacrifice which I would not make to attain eminence in the art of which I have devoted myself." Today his childhood home in Arrow Rock, Missouri is a National Historic Landmark and his paintings now hang as national treasures in museums across the United States. Bingham always believed in his own greatness as an artist and against all odds his life became a hero's journey that ultimately gained the eminence he sought. The year 2011 will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Caleb Bingham, a now firmly established "Old Master" of American Art.

The art historian E.Maurice Bloch (1916-1989) wrote two definitive Catalogues Raisonnes of Bingham's works: "The Drawings of George Caleb Bingham (University of Missouri Press, 1975--out of print) and "The Paintings of George Caleb Bingham" (University of Missouri Press, 1986--out of print). All known works by Bingham up to those times are illustrated or described in the two books. Bloch is considered the most authoritative source for Bingham up to 1986. The George Caleb Bingham Catalogue Raisonne Supplement of Paintings and Drawings, based on Bloch's scholarship and research, was created online in 2005 at "GeorgeCalebBingham.org" and offers a renewed authoritative source directed by art historian Fred R. Kline, the current Editor who, with an Advisory Board including Paul Nagel and William Kloss, seeks to add newly discovered and relocated paintings and drawings to Bingham's body of work, many of which Bloch noted as unlocated or lost based on old records. It is estimated that some 100 paintings by Bingham are still lost: most not described except for a title or the Bingham name, as noted by Bloch, and many others that Bloch simply missed in his accounting which are slowly coming to light. To add to the problem, Bingham did not sign most of his paintings, including many of his masterpieces, among them "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri" (Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)and "The Emigration of Daniel Boone" (Washington University, St. Louis). The Bingham CRS, while currently published online, will be published in the future either as a supplement to the reprinting of the Bloch Catalogues, or separately. It is the first catalogue raisonne of an American artist to be published online, allowing direct public access and communication to an ongoing scholarly project. It has a variety of educational features including a gallery with many of Bingham's notable paintings, an updated biography (with fair use granted for educational purposes), and illustrations of new paintings that have been added to Bingham's body of work.

George Caleb Bingham was born in Augusta County, Virginia on March 20, 1811 on his grandfather's farm (with its prosperous working mill), son of Henry Vest and Mary (Amend) Bingham. In 1819, because of a failed investment, the Bingham family moved to Missouri Territory and young George grew up variously in Franklin, Arrow Rock, and Boonville.

When the Binghams moved to a prospering Franklin in 1819, then just two years established on the banks of the Missouri River, there were still vestiges of Spanish, French, and English influence and Osage Indians roamed the countryside (see "The Concealed Enemy"). Here in 1820, nine-year-old George as he remembered fifty years later was first inspired to be an artist by Chester Harding, who had taken lodging at Henry Bingham's inn The Square and Compass. Harding, who became one of America's finest portraitists, had been in St. Charles County near St. Louis painting a portrait of the aged Daniel Boone, the legendary folk hero whose trailblazing opened up the West for settlement. Having come upriver to Franklin looking for more commissions, Harding was also putting the finishing touches to the Boone portrait. Young George, already showing signs of drawing ability and having an interest in art, was assigned by his father to assist Harding in his needs as he daily worked on the Boone portrait. George no doubt had the exciting opportunity as well to study the various sketches and paintings the artist carried with him. Bingham later in life wrote: "The wonder and delight with which Harding's works filled my mind impressed them indelibly upon my then unburdened memory."

In 1823, George's father Henry Bingham died of malaria. This tragedy left his wife Mary and their children little else but their farm across the river from Franklin in Saline County, near Arrow Rock, fortunately where Henry's brother John and his family had recently settled.

During the next five years in Arrow Rock, young George was reportedly tutored by Rev. Jesse Green, a cabinet maker and Methodist minister. From 1828-32, George lived in nearby Boonville, apprenticed to Rev. Justinian Williams (yet another cabinet maker who was also a Methodist minister). The early influences of woodworking with its attendant strict craftsmanship and geometric constructions, as well as that of Biblical literature with its moral teachings and rich narratives, may suggest further insights into the early development of Bingham's artistic consciousness.

As he matured into his teens, George also gave serious consideration to the professions of lawyer and preacher (which he had personally practiced, preaching here and there as a student of the two Reverends). These early ambitions could be seen to characterize his enduring combative and moralistic personality. However, the idea of becoming a painter interrupted these musings and began to materialize as a result of a second meeting, during his apprenticeship in Boonville, with his old friend Chester Harding who gave him some brushes and urged him to try his hand at painting a portrait.

Bingham's artistic career as a self taught portrait painter began in earnest a little later in Arrow Rock. His early style of portraiture, seen in 1834-40 examples, were skillfully crafted, strongly characterized, and far superior to the work of most provincial artists of the period. His later portraits from the 1840s into the 1870s generally conveyed a softer tone and a straighforward likeness. Many, from his early to his late period, stand as exceptional studies of their subjects.

Perhaps the fine quality of the two late examples could be tied additionally to the affection George had for Rollins and Ream. By 1878, near the end of his life, Bingham had painted close to 500 portraits.

Portraiture was by far George's most prolific artistic genre, producing a steady income throughout his career and "kept the pot boiling", as the artist acknowledged. But he also admitted to the pleasures of friendship and personal relations that developed from painting portraits and he unquestionably gained social status from the outset of his career by his choice of subjects, most of whom represented a veritable Who's Who of 19th century Missourians. Most important among Bingham's portrait-fostered friendships was one that established an extraordinary lifelong bond with Major James Sidney Rollins, a practicing Columbia, Missouri lawyer close in age to George, whose portrait the artist first painted in 1834. Rollins a wealthy and powerful Missouri politician and "Father of the University of Missouri" was Bingham's first patron and he went on to become a brotherly confidant, advisor, political ally, and financial backer to the end of Bingham's life. In excerpts from several late letters, an ailing Bingham writes to Rollins: "I shall never be able to repay you for a ...friendship such as few men have the good fortune to be blessed with on this earth...No man could be blessed with a truer and more constant friend that I have ever found in yourself ...[a friend who had always given him ]...the tenderest solicitude of a brother."

In 1845 Bingham began the series of narrative scenes of frontier life upon which his reputation rests. "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri", the earliest of his masterworks, is still considered his best and most iconic painting. It is also the simplest of his multifigure scenes: it depicts a grizzled pipe-smoking fur trader, a smiling youth, and a tethered baby bear, all posed in a long thin dugout canoe. Out of the wilderness they come, gliding silently and eternally by on the placid water, gazing at you and you at them. Indeed, the painting may have been animated in Bingham's mind like a scene from the moving-picture "panoramas" of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, in vogue since the first 1839-40 exhibitions in nearby Louisville which George possibly attended during a political trip to Washington, D.C. Bingham traveled constantly and big cities like St. Louis, Philadelphia, Washington, New York were familiar environments where he worked and lived and found artistic stimulation.

Riverboatmen, considered a rough and carefree bunch, were a more familiar sight than fur traders. In his first depiction of them "The Jolly Flatboatmen" (1846) Bingham showed the hard working boatmen enjoying themselves as their day on the river begins. With their celebration invitingly filling most of the picture plane, the spectator glides along behind them enjoying the moment. Its vicarious joy is irresistible; its classically organized and finely crafted composition becomes for the viewer a clear and memorable image.

It is instructive to recognize in regard to Bingham's style that no 19th century American artist created paintings with a more conscious geometrical structure of forms or with a more conscious embrace of the classical Renaissance tradition, a tradition which importantly stressed the artist's use of model drawings. Bingham used figurative drawings as an integral part of his painting procedure; sometimes as side by side models, sometimes as transfer drawings which were traced onto primed canvas. His drawings went with him everywhere as precious sources for his paintings.

Self taught, Bingham learned deep lessons from the old masters which he no doubt first experienced as prints, perhaps after Raphael's paintings or Greco-Roman sculpture or from instruction books like Francis Nicholson's "The Practice of Drawing and Painting Landscapes from Nature..."(1823). Nicholson cited landscape models such as Poussin, Claude, Salvator Rosa and Richard Wilson, and offered such instructions as: "The foundation of drawing and painting from nature should be laid by studying and copying the works of the best masters, in order to ascertain the methods of practice, and principles of construction. With such assistance, the learner will acquire the power of seeing what is most perfect in nature..."

Notable examples of Bingham's landscape paintings emerge particularly from the early 1850s in a variety of styles. "The Storm", "Horse Thief", and "Deer in Stormy Landscape" all suggest a strong direction from Thomas Cole and the period of the Cole revival after the artist's early and widely lamented death in 1848, with "Horse Thief" coming closest to Cole's allegorical landscapes. In a more conservative direction, closer to English country scenes and American counterparts like Joshua Shaw, Thomas Doughty, and Asher Durand, "Landscape with Waterwheel and Boy Fishing" and "View of a Lake in the Mountains" offer fine examples and suggest youthful reveries drawn from Bingham's growing up in Virginia and Missouri. As only 25 of Bingham's 50 recorded landscapes have been located, his complete achievement in this field, in which he ranged widely, must await a later judgment.

Poussin's works clearly inspired Bingham's thinking about figural compositions, as well as about landscape. George learned well from the masters: his compositions with figures are exceptionally well organized and skillfully posed; his landscapes are arranged clearly and distinctly. Pyramidal formations of figures and a balanced geometrical construction consistently bring a classical order to Bingham's narrative and landscape paintings. His style could be succinctly stated a straightforward realistic manner based on geometrical principles and classical models.

Bingham was inspired by many artistic predecessors but his genius invariably transformed suggestion from others into his own original statement.

Starting in 1847 and in a more developed way in the early 1850s, Bingham began his "Election" series of paintings illustrating America's democratic process and the political life of the Western frontier. The success of these election pictures in their public exhibitions encouraged Bingham to commission engravings of them and this continued to spread his fame around the nation. These prints also importantly supported and illustrated the notion of Missouri's coming of age within the American political framework, having just become a state in 1820 . A number of Bingham's political pictures exist in duplicate since he made one copy available for exhibition while a second was in the hands of an engraver.

Two of the most notable Election pictures "The County Election" and "The Verdict of the People" involved dozens of carefully organized interacting figures, many of which were modeled from drawings that illustrated a wide variety of people of many physical types, ages, facial features, expressions, and body positions. The drawings with very little variation in size would then be creatively placed, transferred or modeled onto the canvas, and then painted. Bingham's artistic method throughout his career involved use of a portfolio of model drawings, almost all of them figurative, many of which he reused interchangeably. Virtually all of Bingham's extant drawings are deposited in museums across Missouri.

Surprisingly, little evidence of preliminary landscape or portrait sketches have been found, suggesting George must have painted or drew the landscape elements and portraits directly onto the canvas. It is probable that he also used available photographs to assist with some of his portrait subjects after 1847.

The existence of Bingham's own early use of photographic records, beginning in 1847 with daguerreotypes of a few of his important paintings, points to an unusual and possibly unique procedure for an American artist of the period. By so doing, Bingham preserved the appearance of a lost picture, "The Stump Orator" (1847) the earliest of the Election series and in all likelihood used its photographic record along with saved drawings to reconstruct this complicated composition as a new work in 1853-54 titled "Stump Speaking".

The political genre undoubtedly drew Bingham to study the series of election subjects by the famous English artists William Hogarth (1697-1764) and Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841), from whose widely reproduced works he clearly found inspiration. While Bingham's paintings do not have the wholly satirical overtones of Hogarth's, they do have an honest social and political presence of real, imperfect, and animated people interacting in what his French contemporary Balzac called "The Human Comedy". The paintings no doubt drawn from Bingham's own well considered experiences as voter, party worker, and elected politician reflect the rough hewn political life of Missouri frontier towns and other American places.

Bingham's genre and landscape paintings of the "exotic West" became popular in the East largely due to the support of the influential New York-based American Art-Union (active 1839-51). The AAU purchased and distributed George's paintings, and occasionally distributed engravings of them, to a national membership by lottery. The AAU had a fee-based membership which by 1849 numbered close to 20,000 members. Each year, members received an engraving of a painting by an American artist as well as a chance to win an original painting or sculpture at an annual lottery. Artists were also invited to exhibit and sell works at the gallery in New York City. Bingham's commercial success began at the AAU in 1845 with their purchase of "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri" and "The Concealed Enemy" as well as two landscapes "Cottage Scenery" and "Landscape: Rural Scenery". In 1846, "Jolly Flatboatmen" was purchased and gained enormous national popularity when it was engraved and distributed in 1847 to 10,000 subscribers. In a seven year period, the AAU purchased twenty of George's paintings. Along with Bingham, the AAU helped further the careers of William Sidney Mount, Richard Caton Woodville, George Inness, and Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze.

Although his life was dedicated primarily to painting, Bingham was always acutely aware of the significant events in the nation's evolving history and, on more than one occasion, felt impelled to be something more than an armchair observer. His early self-taught training in law and his skill as a public speaker prepared him for the political arena, but it was more his deep-rooted moral convictions about right and wrong and a strong sense of public duty that stimulated him from time to time to leave his chosen career and seek public office and work for the public good. Highlights of Bingham's political career, not including the many times he was a candidate for public office, can be briefly summarized: 1848, elected to a seat in the Missouri state legislature as representative from Saline County; 1862-1865, during the Civil War, appointed Missouri state treasurer; 1874, appointed president of Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners; 1875, appointed adjutant-general of Missouri by the governor (which led to his being called "General Bingham" toward the end of his life).

In 1856, Bingham with his wife and daughter Clara sailed for Europe, first to Paris, which he found alien and inhospitable and expensive and even the Louvre disconcerting. George and his family then went on to a sojourn in Dusseldorf, where he completed full-length portraits of Washington and Jefferson (a commission from the Missouri State Legislature, both now destroyed by fire); the second of three related flatboatmen paintings, "Jolly Flatboatmen in Port" (1857); "Moonlight Scene: Castle on the Rhine"(1857, Private Collection); and probably other unrecorded works.

Dusseldorf , compared to Paris, was a manageable city of 30,000 and a famous art center that had attracted, interestingly enough, such aspiring German-American artists as Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Carl Wimar, and Albert Bierstadt all of whom had been born in Germany and emigrated to the United States as children, only to return to Germany to study and in Leutze's case to live in Dusseldorf for many years where he also became a noted teacher. From the 1840s through the 1850s other American artists such as T. Worthington Woodridge, Richard Caton Woodville, and Eastman Johnson also studied in Dusseldorf. Leutze, as teacher and great friend of visiting American artists, was a first stop for American expatriates, and Bingham, although a mature and established painter, was no exception. George wrote to his friend Rollins back in Columbia, Missouri: "Immediately upon our arrival in Dusseldorf, I called upon Leutze, the famous painter, who received me as cordially as if I had been a brother, and without a moment's delay assisted me in finding a Studio, and introduced me to one of his American pupils through whose guidance I shortly obtained accommodations of the best kind, and upon the most reasonable terms."

Upon his somewhat reluctant return to the United States in 1859 in the wake of the death of his wife Eliza's father Bingham became increasingly busy in Missouri with politics. Most of his diminishing artistic production consisted of portrait commissions, with an occasional genre or history painting, most notably the legendary "Martial Law or Order No. 11". George continued to live a restless nomadic life, constantly traveling in search of portrait commissions, and residing all over Missouri.

In 1877, thanks once again to Rollins, Bingham now in poor health was appointed the first Professor of Art at the University of Missouri's newly established School of Art in Columbia, a largely honorary position that allowed students to observe him at the easel from time to time and to seek limited instruction.

Weakened from a bout with pneumonia in February 1879 and in fragile health thereafter, Bingham died at age 68 in his home in Kansas City on July 7, from "cholera morbus" (a disease, it is noted, that is usually caused by imprudence in diet or by gastrointestinal disturbance).

George Caleb Bingham is buried in the Union Cemetery in Kansas City under a tall monument commissioned by his third wife, the notable Mattie Livingston Lykins. The monument bears a medallion-like portrait bust of the artist carved in relief and an almost obscured inscription: "Eminently gifted, almost unaided he won such distinction in his profession that he is known as the Missouri artist." In an 1837 letter to James Rollins, Bingham wrote his credo at the beginning of his career: "There is no honorable sacrifice which I would not make to attain eminence in the art of which I have devoted myself." Today his childhood home in Arrow Rock, Missouri is a National Historic Landmark and his paintings now hang as national treasures in museums across the United States. Bingham always believed in his own greatness as an artist and against all odds his life became a hero's journey that ultimately gained the eminence he sought. The year 2011 will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of George Caleb Bingham, a now firmly established "Old Master" of American Art.

The art historian E.Maurice Bloch (1916-1989) wrote two definitive Catalogues Raisonnes of Bingham's works: "The Drawings of George Caleb Bingham (University of Missouri Press, 1975--out of print) and "The Paintings of George Caleb Bingham" (University of Missouri Press, 1986--out of print). All known works by Bingham up to those times are illustrated or described in the two books. Bloch is considered the most authoritative source for Bingham up to 1986. The George Caleb Bingham Catalogue Raisonne Supplement of Paintings and Drawings, based on Bloch's scholarship and research, was created online in 2005 at "GeorgeCalebBingham.org" and offers a renewed authoritative source directed by art historian Fred R. Kline, the current Editor who, with an Advisory Board including Paul Nagel and William Kloss, seeks to add newly discovered and relocated paintings and drawings to Bingham's body of work, many of which Bloch noted as unlocated or lost based on old records. It is estimated that some 100 paintings by Bingham are still lost: most not described except for a title or the Bingham name, as noted by Bloch, and many others that Bloch simply missed in his accounting which are slowly coming to light. To add to the problem, Bingham did not sign most of his paintings, including many of his masterpieces, among them "Fur Traders Descending the Missouri" (Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)and "The Emigration of Daniel Boone" (Washington University, St. Louis). The Bingham CRS, while currently published online, will be published in the future either as a supplement to the reprinting of the Bloch Catalogues, or separately. It is the first catalogue raisonne of an American artist to be published online, allowing direct public access and communication to an ongoing scholarly project. It has a variety of educational features including a gallery with many of Bingham's notable paintings, an updated biography (with fair use granted for educational purposes), and illustrations of new paintings that have been added to Bingham's body of work.

3 George Caleb Bingham Paintings

Cottage Scene 1845

Oil Painting

$1240

$1240

Canvas Print

$85.62

$85.62

SKU: BGC-8754

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 64.8 x 76.2 cm

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 64.8 x 76.2 cm

Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

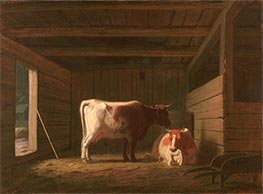

Daybreak in a Stable c.1850/51

Oil Painting

$699

$699

Canvas Print

$73.13

$73.13

SKU: BGC-18650

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 45.7 x 62 cm

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, USA

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 45.7 x 62 cm

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, USA

Colonel Thomas Miller c.1834

Oil Painting

$758

$758

Canvas Print

$81.47

$81.47

SKU: BGC-18651

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 70.5 x 58.4 cm

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, USA

George Caleb Bingham

Original Size: 70.5 x 58.4 cm

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, USA